**This is from a UC Berkeley course project, so the source code is not publicly viewable. If you are an employer interested in viewing my project code, please contact me privately.**

In this project, I created a rasterizer that can take vector images (.svg files) and render them into pixel images on a screen and .png files. Some of the viewing options available include supersampling, hierarchical transforms, linear interpolation with barycentric coordinates, and methods of pixel and level sampling for texture maps. Actually implementing the formulas and data structures described in lecture gave me a better understanding of the complexity of rendering even simple shapes. Having the visual feedback and thinking about runtime when trying out different combinations of options helped me solidify my understanding of the tradeoffs between the different methods.

Rasterizing is the process of taking shape information and converting that into an image by determining which pixels

will be colored.

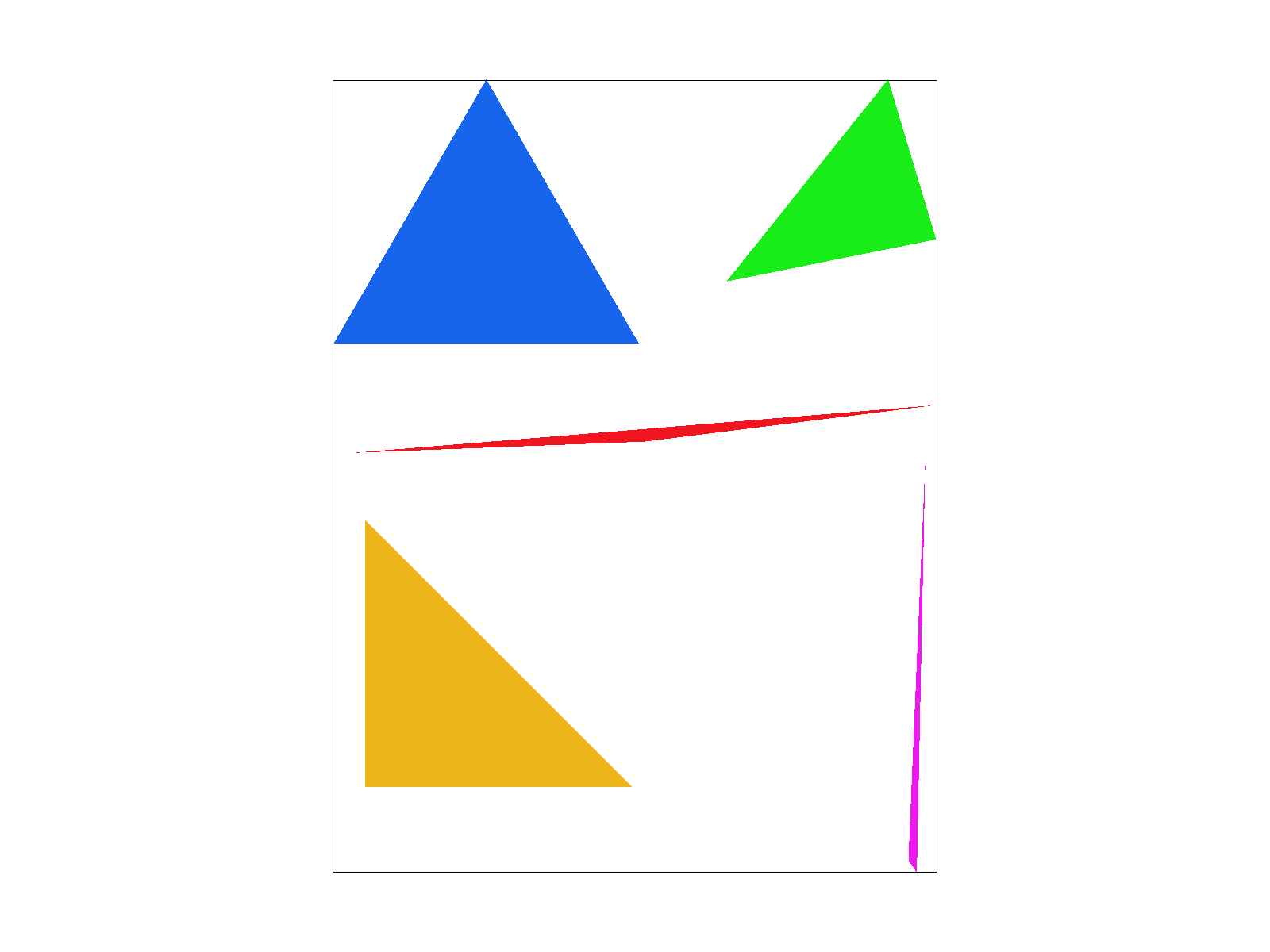

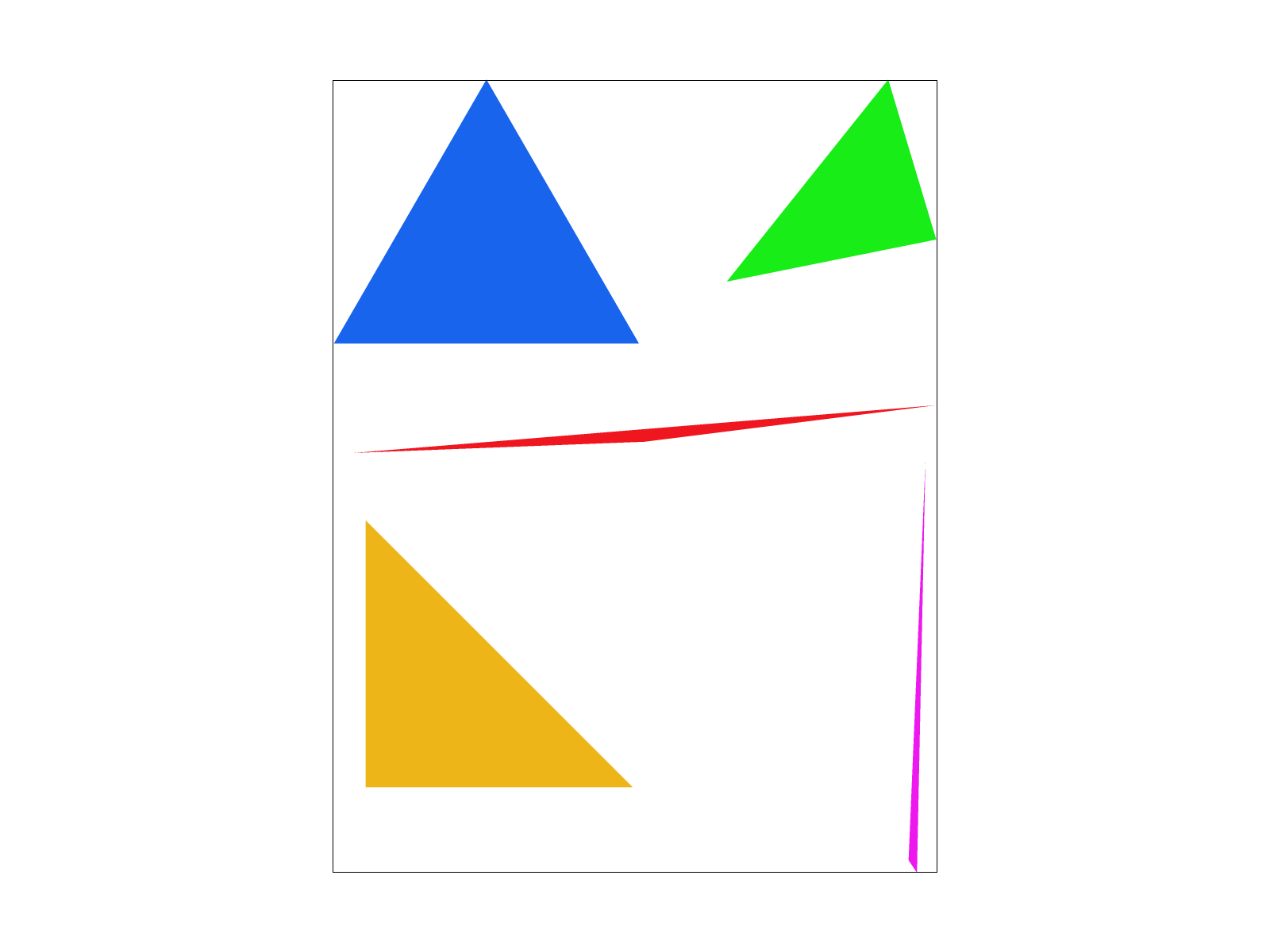

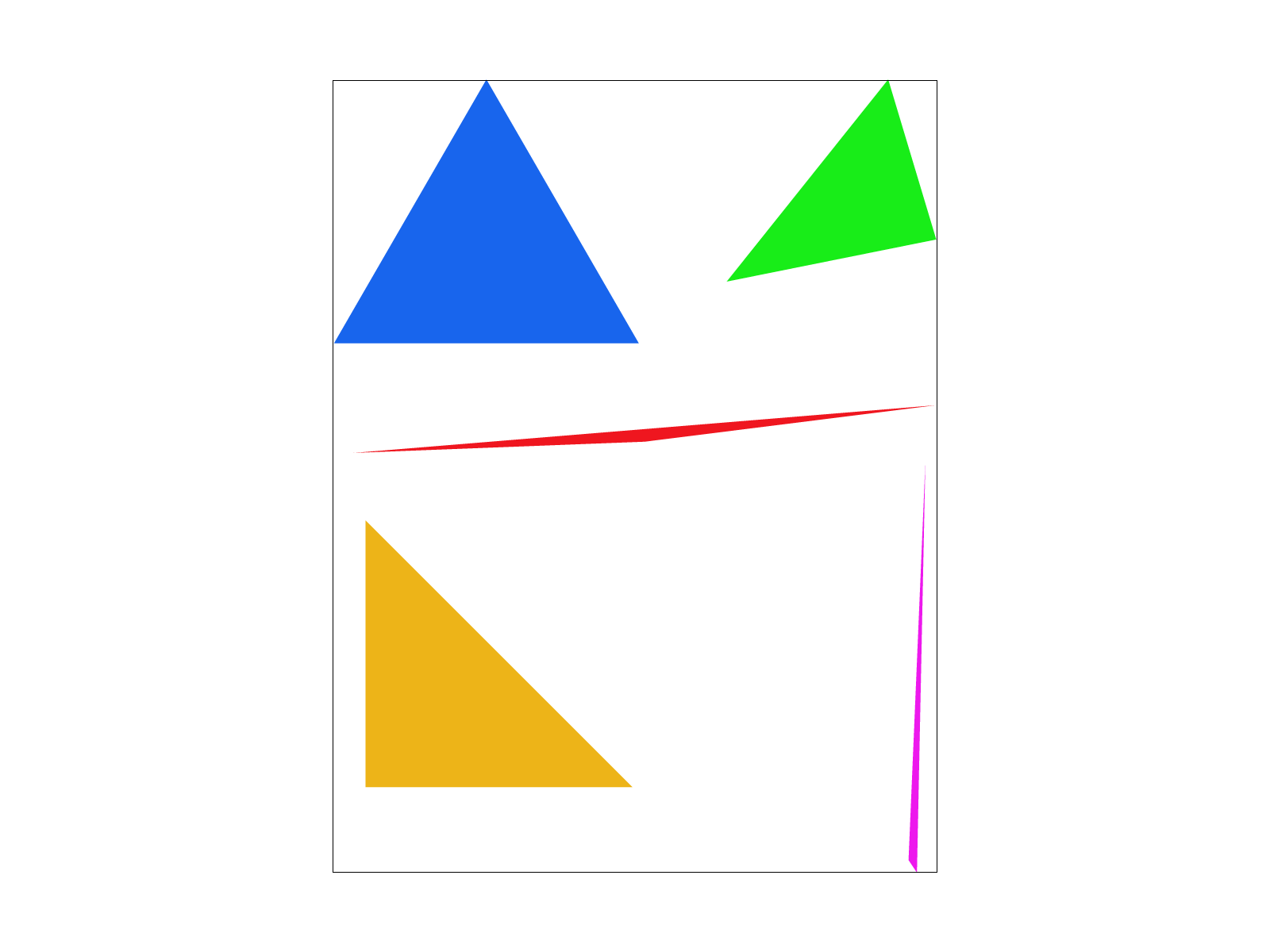

In this part, the function for rasterizing triangles takes in a color and 3 \((x,y)\) points which are the vertices of

the triangle

and colors the pixels within the triangle.

The algorithm I used checks each pixel within the bounding box of the triangle (from the minimum to maximum \(x\) and the minimum to maximum \(y\) of the vertices). For each of these pixels, I determined whether it was within the triangle by testing the pixel (with 0.5 added to each integer coordinate to represent the middle of a square if the pixel coordinates are points on a grid) against the line equations \(L_i(x, y) = -(x-X_i)*(Y_{i+1}-Y_i) + (y-Y_i)*(X_{i+1}-X_i)\) where \((x,y)\) is the point being checked and the coordinates of the vertices are \(X_i, Y_i\). The line equations check which half plane created by a line that the point lies on. Therefore, I needed to do 3 line equation checks for the 3 vertices. Because the formulation assumes an ordering of the vertices, I also needed to do another 3 checks for the opposite winding order. Depending on the value of \(L_i(x, y) = 0\) means the point is on the line, \(> 0\) means the point is inside the edge, and \(< 0\) means the point is outside the edge. The simple edge behavior used was rendering pixels on the line as within the triangle.

There are some obvious aliasing effects ("jaggies"), especially in the red and pink triangles, which will be improved in the next step...

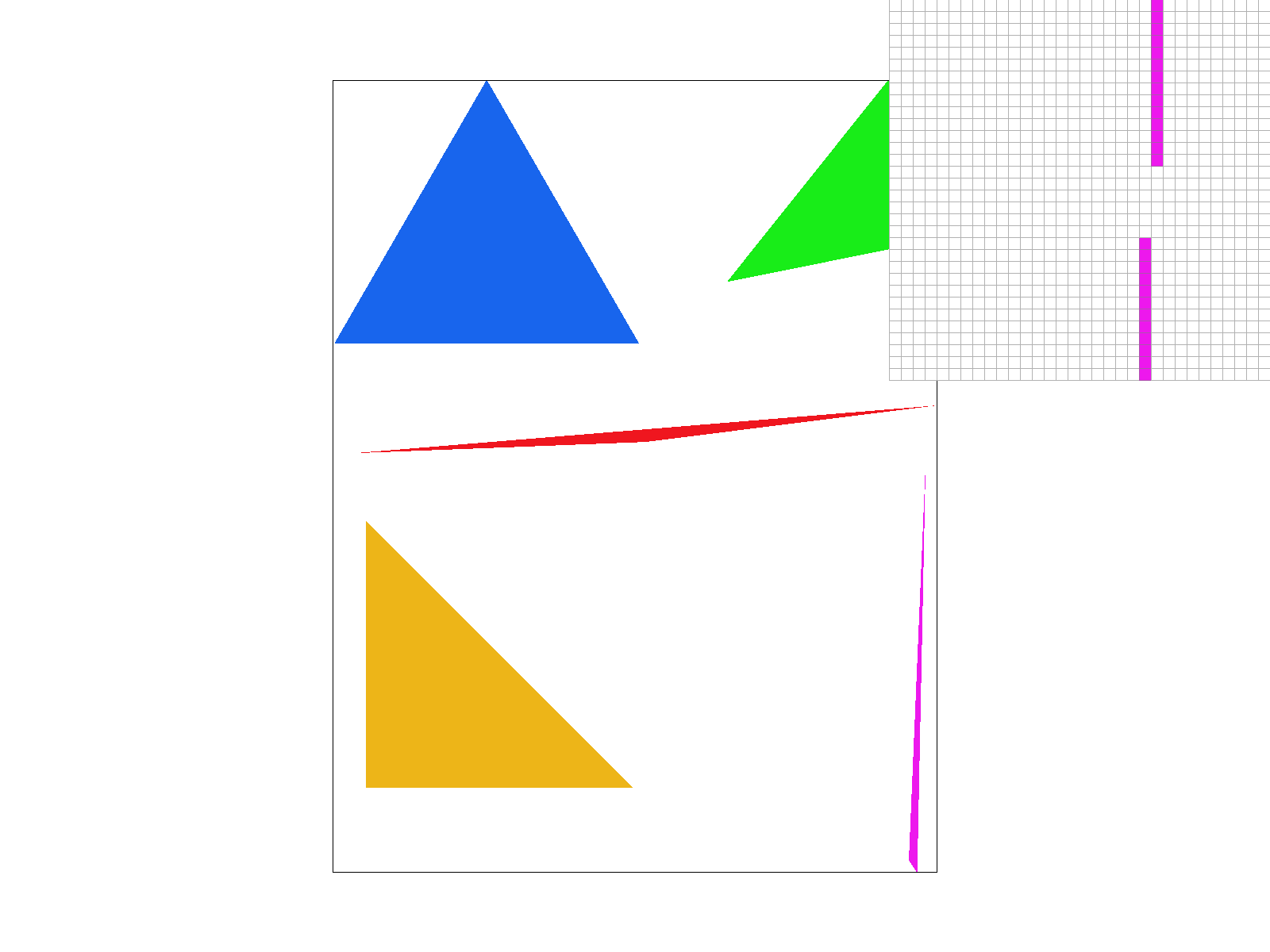

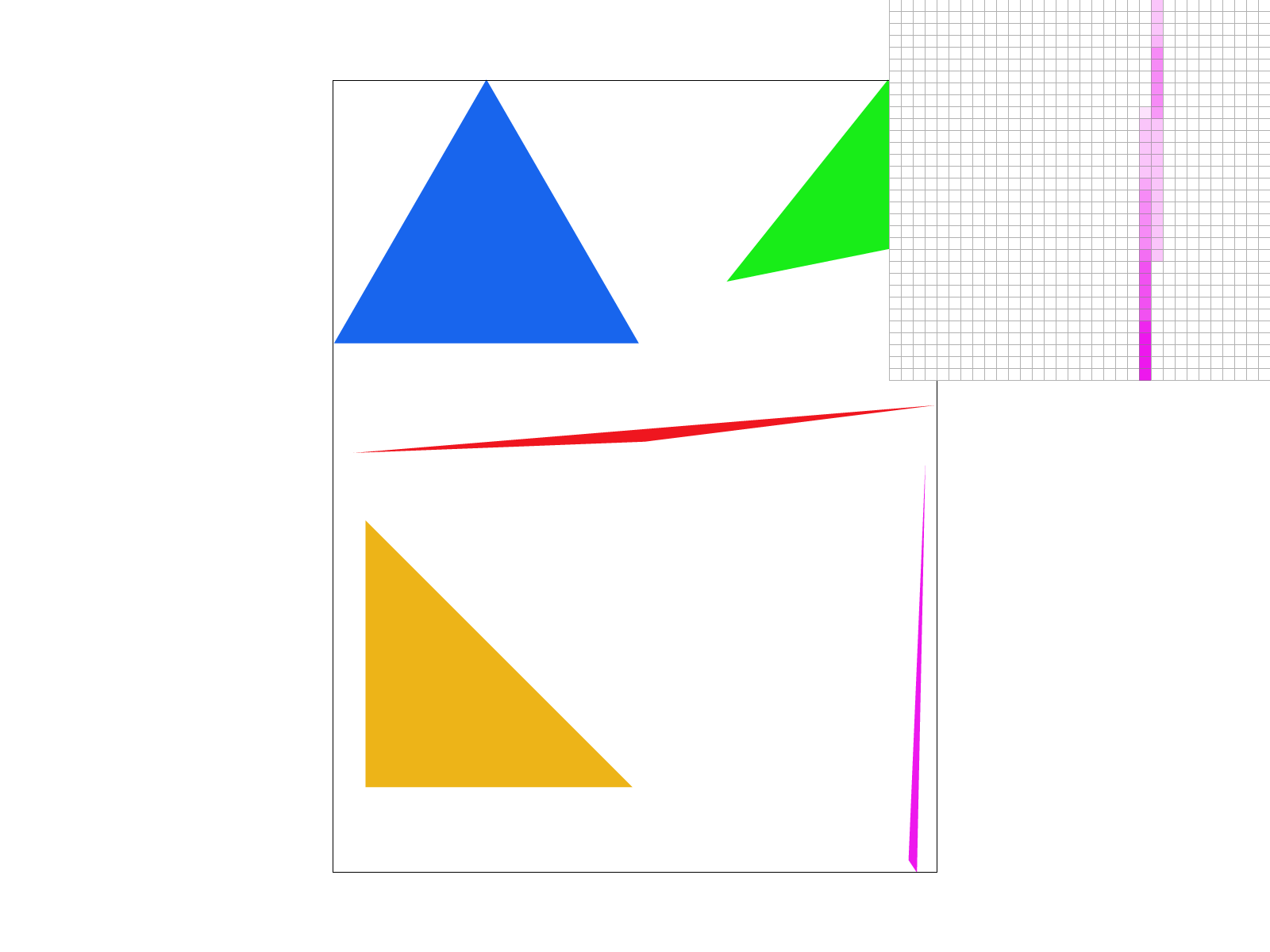

sqrt(sample_rate)samples in each dimension for a total of sample_rate samples that are color averaged into a final single pixel in the framebuffer. This introduced a new buffer to the rendering pipeline containing the Color at each of the supersampled values. Supersampling therefore reduces aliasing artifacts, creating smoother edges at the cost of more required memory for the supersampling buffer.

|

|

|

|

Zooming in with the pixel inspector, we can see the difference on the thin tip of the pink triangle. In the non supersampled image (rate of 1 per pixel), there is a discontinuity, but when supersampled at a rate of 16 per pixel, there is no discontinuity. Without supersampling, when the tip of the triangle becomes very thin, it sometimes does not intersect the middle of the pixel (x+0.5, y+0.5), so there is a discontinuity. When supersampling, at least some of the supersamples within the pixel intersect the middle of the triangle, so they partially weight the color of the triangle so there isn't a completely white discontinuity.

|

|

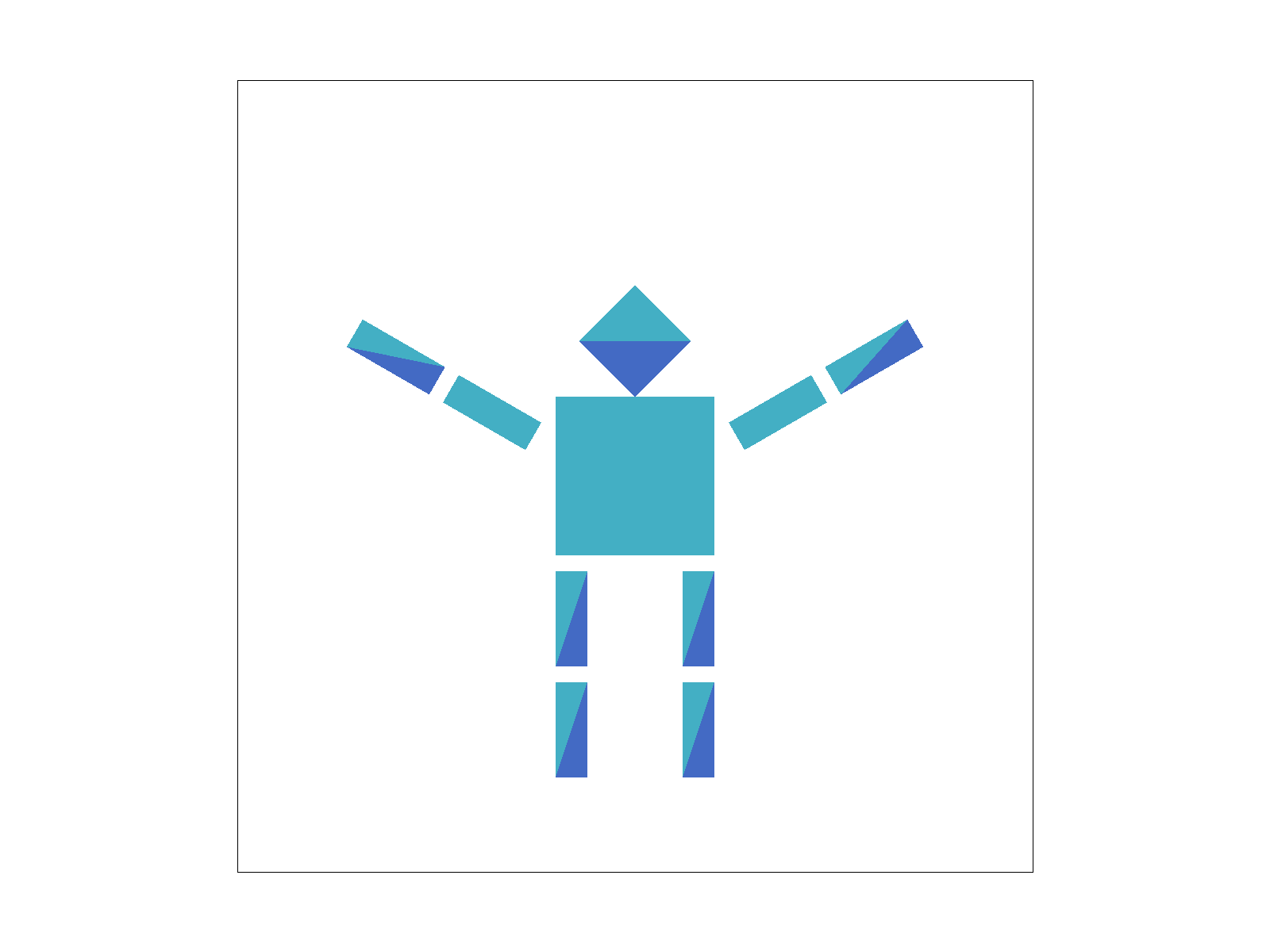

In this section, I implemented 3 basic transforms (translate, scale, and rotate) using transform matrices in homogenous coordinates.

To demonstrate the capabilities of these transforms, I created my_robot.svg. I wanted to add more expression to it, so I rotated the arms to be raised, added another color suggesting hands, translated the head down to touch the torso, and flipped (combination of rotation and translation) the left leg so the shadows would be on the same side as the right one.

|

|

|

|

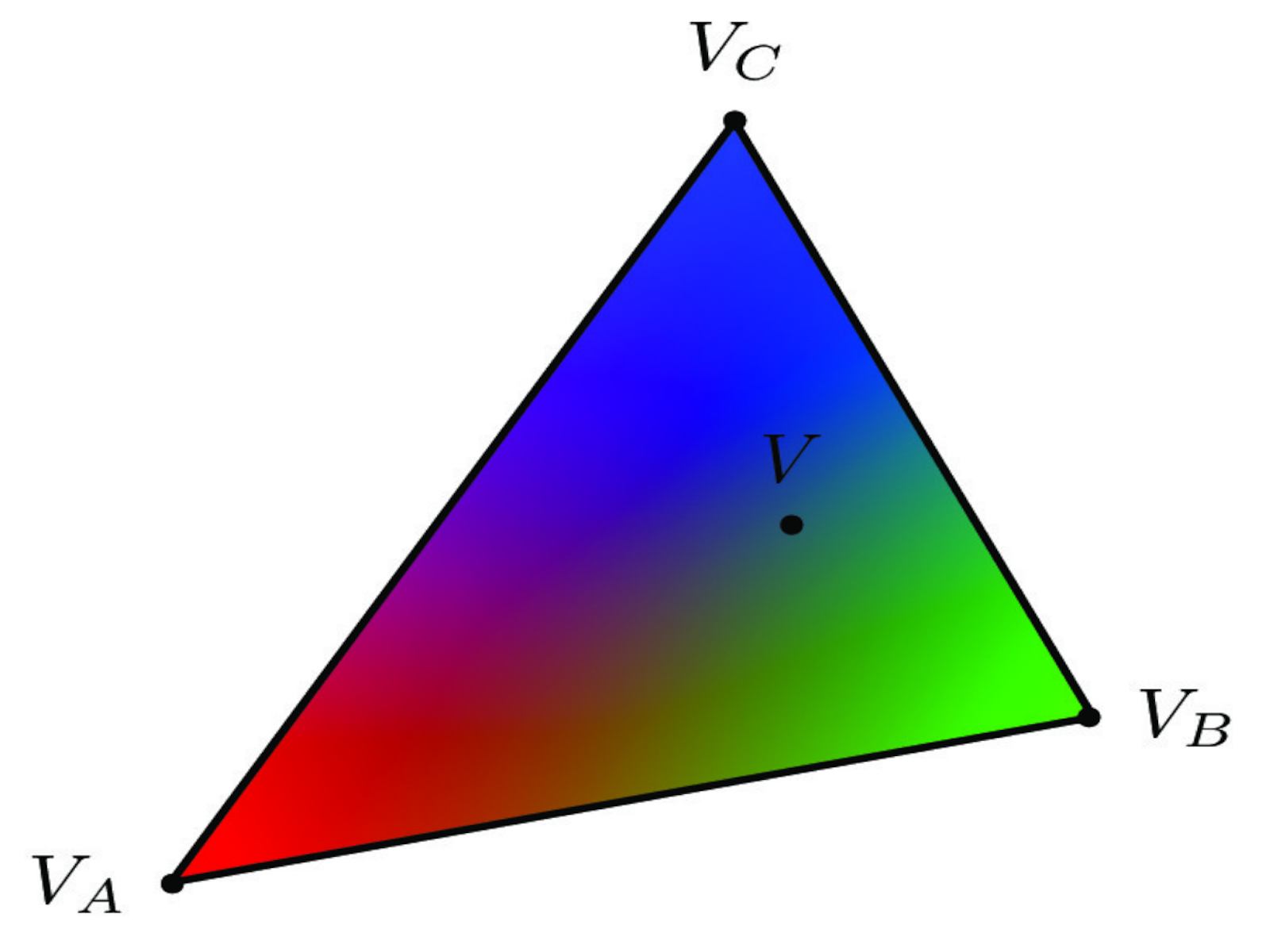

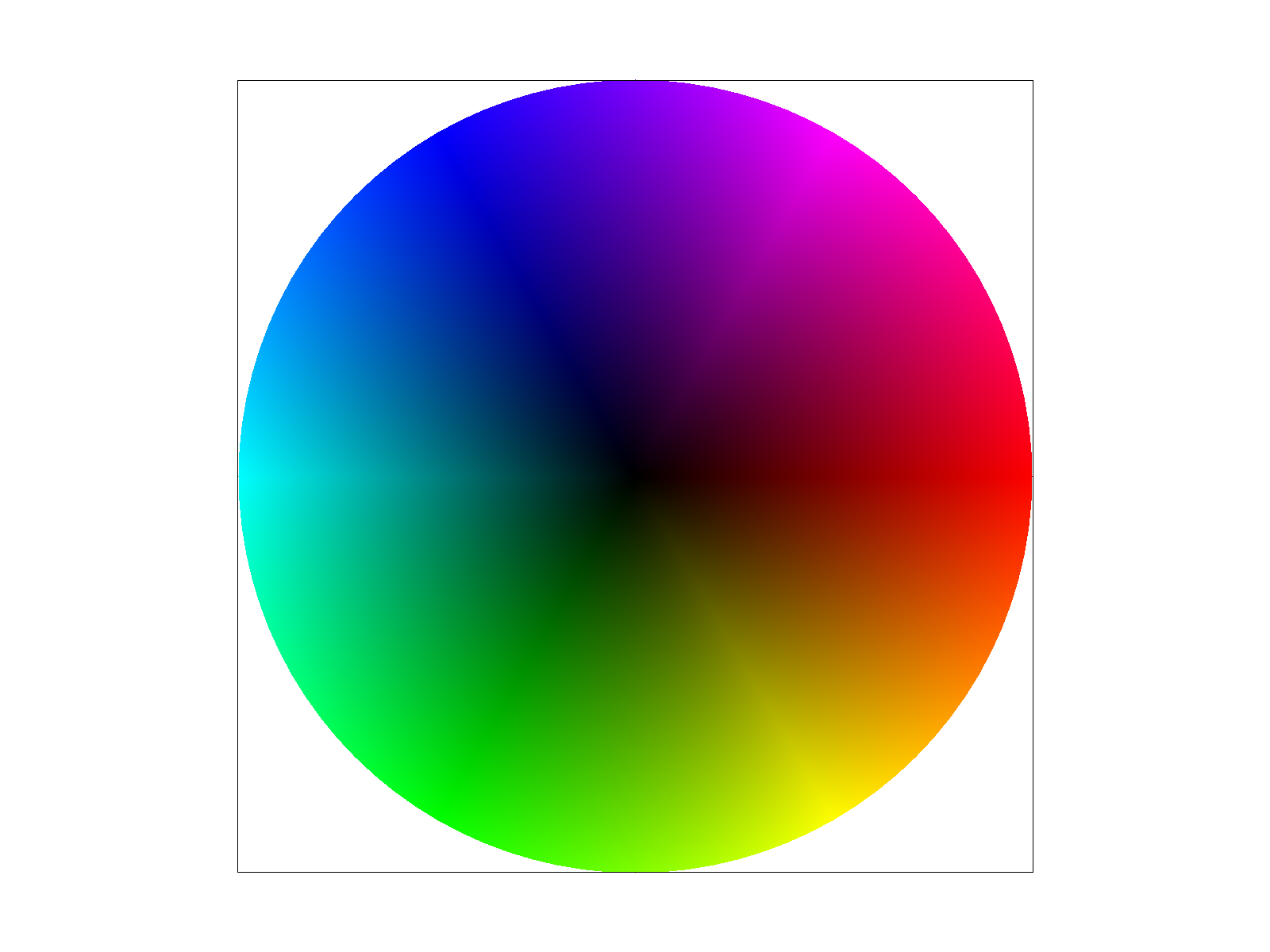

Instead of just interpolating colors given at different vertices, we now have a texture map that tells us what color values should be used. But since the dimensions of the texture map and image don't necessarily match, this is another sampling problem as we need to sample the texture map at the corresponding location for each pixel in the image.

Because we are given the corresponding \((u, v)\) texture coordinates for each of the vertices of the triangle in the image, I used barycentric coordinates to interpolate the texture coordinates for each point within the triangle. The texture coordinates range from 0 to 1, so I multiplied them by the width and height of the texture map to get the actual sample coordinates. In the nearest sampling method, I simply rounded to the nearest sample.

The bilinear interpolation method, takes into account the value of the 4 nearest texels by performing 3 linear interpolations (2 in x and 1 in y) and weighting each of their color values accordingly. There is a larger difference between the two sampling methods in levels with more detail, which often corresponds to higher frequencies.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(also known as trilinear texture filtering). |